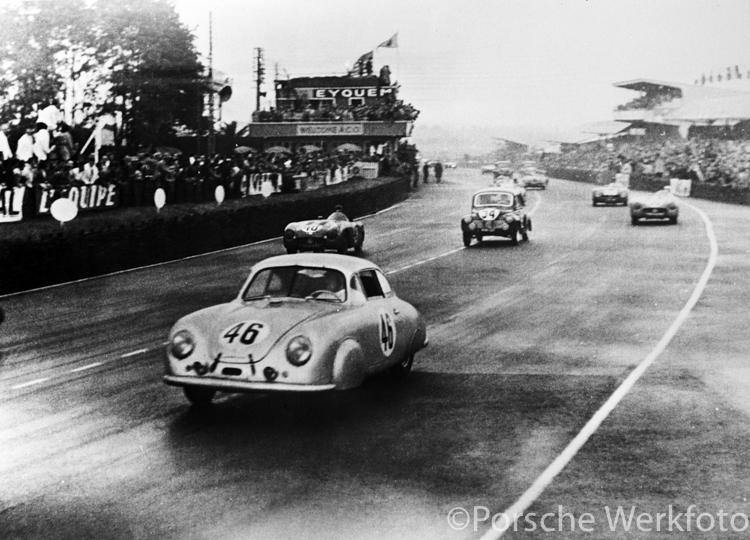

The date was 23 June 1951, and sixty race cars lined up at 16h00 for the start of the nineteenth running of the Le Mans 24 Hour race. This would be the first race for the Porsche 356 SL at Le Mans, in fact it was the Stuttgart company’s first foray into big time international motorsport, so a lot was riding on the 356’s performance.

It was customary for the cars to line up on the pit garage side of the track in order of decreasing engine cubic capacity, while the drivers positioned themselves opposite their car on the other side of the track. This system of starting was used between 1925 and 1962, and it was only from 1963 onwards that the cars were ordered in accordance with their times set in practice.

Two 356 SLs were entered in the 1951 Le Mans 24 Hour race, but we are getting ahead of ourselves, because the story of how this came about requires telling. In 1944, Porsche moved its operation to the unlikely location in a sawmill in Gmünd, Carinthia in Austria, in an effort to escape the Allied bombing of the industrial city of Stuttgart. It had been the dream of Professor Ferdinand Porsche and his son Ferry, to build a sports car bearing the family name, but Stuttgart seemed just too risky a city in which to do that. And so, just two years after the cessation of hostilities in Europe, in the summer of 1947, the first drawings of Porsche’s dream car began to take shape in their temporary mountain headquarters.

The first sports car to carry the Porsche name was duly registered on 6 June 1948, and was given the moniker 356/1. This prototype was a one-off and featured a mid-mounted engine, but before the first 356/1 had even been completed, Ferry Porsche anticipated that the method of hand-beaten aluminium panels stretched over a tubular frame was too expensive for a full-scale production model. The plans for a revised model began immediately, and production of the rear-engined 356/2 model followed soon after at Porsche’s facilities in the sawmill.

During 1948/1949, a total of 53 aluminium bodied 356s were produced featuring a sheet steel box frame, and these models became known as the Gmünd cars. In 1949 Porsche commissioned body builders Reutter in Stuttgart, to construct 500 bodies in steel as aluminium was hard to source at that time. The contract with Reutter coincided with Porsche’s move back to Stuttgart, and despite the upheaval of the move, Porsche had the foresight to retain five of the 53 Gmünd cars for its own motorsport ambitions.

Although Porsche had no formal motorsport department, Ferry Porsche realised that the route to increased sales lay in racing victories. This would alleviate the need for costly advertising campaigns, as it was his perception that victories on the race track would be well covered by the motoring press, and this would serve as their advertising. Ferry Porsche’s bold and momentous decision to go racing, was the first step that would launch the fledgling company into the racing spotlight, and which in time would bring them significant international recognition and rich rewards.

A meeting between Ferdinand and Ferry Porsche, and Charles Faroux, the Le Mans race organiser, took place at the 1950 Geneva Motor Show. At this meeting, it was agreed that Porsche would enter two cars in the 1951 race. This would be the third running of the French endurance race since the end of the War, which also made Porsche the first German motor manufacturer to enter the race after the War. It was decided to use the aluminium-bodied 356 Gmünd cars for the race as they possessed both weight and aerodynamic advantages over the steel-bodied cars manufactured by Reutters in Stuttgart. The weight advantage was rather obvious with aluminium being lighter than steel, but the aerodynamic advantage came about because the cabin structure was narrower than the Stuttgart-manufactured cars.

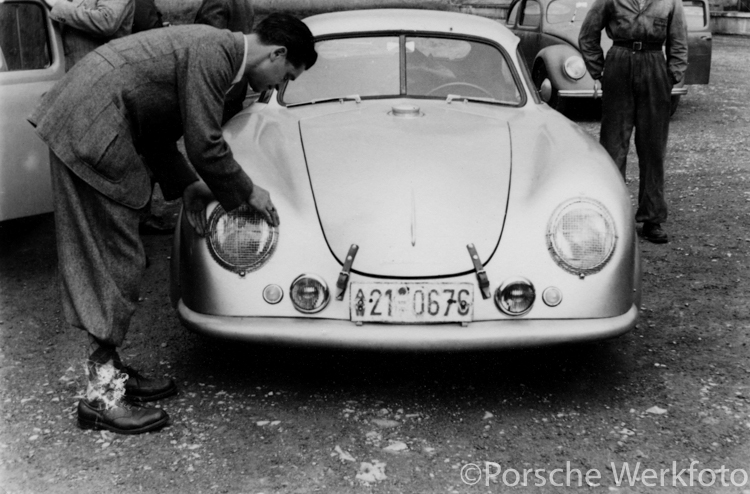

Powering the 356 SL was a 4-cylinder VW-derived boxer engine that developed 46bhp and gave the car a top speed of around 160km/h. Performance was sprightly thanks to Porsche’s ‘light but nimble’ philosophy, a hallmark that the company carried with it for many years. Indeed, the little car’s ‘SL’ moniker stood for ‘Super Leicht’ (Super Light). The 356 SL featured louvered blanking plates in place of the rear quarter light windows, and the wheel openings were covered by streamlined fairings. Hydraulic brakes replaced the cable-actuated drum brake system that was fitted to the Gmünd 356 cars. While the body panels were fabricated from aluminium, the chassis and doors were made of steel.

356 SL race preparations

Three cars were prepared for the 1951 Le Mans race, and these were: chassis 356/2-054, 356/2-055 and 356/2-063. According to a factory workshop memorandum dated 24 March 1951, a larger petrol tank was ordered and installed in each car. The front brake drums were fitted with a small air scoop which was attached to the back of the drum and directed cool air to the brakes. The underneath of the car was fitted with underbody aluminium panels to smooth the flow of air under the car. Considering that the roof structure was simple aluminium, and the car was devoid of any internal roll bars or seat belts, one can only admire the bravery of the drivers.

The engine cover at the rear had its internal hinge and spring assemblies removed as they interfered with the higher downdraught carburettors. Instead, a pair of external hinges were fitted with a spring-loaded catch at the bottom of the cover. On the inside of the engine cover, a substantial reinforcing panel had two large round holes cut into it to improve the flow of air into the engine compartment. The front bonnet was secured by two leather straps at its front end, allowing access to this compartment from the outside. Fuel was filled into the larger front mounted tank by way of a centrally located filler cap that protruded through the bonnet.

Considerable work was done to reduce weight in the car, and to this end the heater system was removed, while a lightened flywheel was also fitted. But on the other hand, carpeting was retained in the car as was the cigarette lighter, as well as an additional coil in the engine bay and an electric fuel pump which was fitted to the inside driver’s side kick panel. To better cope with the rigours of 24-hour racing, Hemscheidt dual action telescopic dampers were fitted at the front. In order for these to be fitted, certain body modifications to be made, which took a further 14 days.

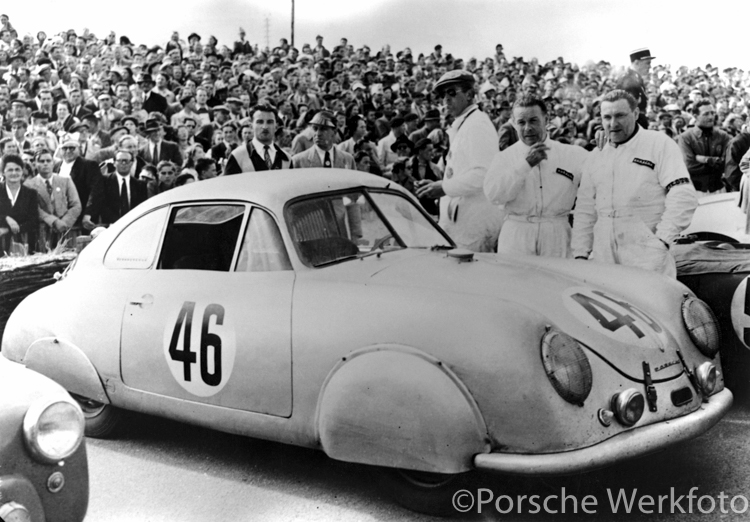

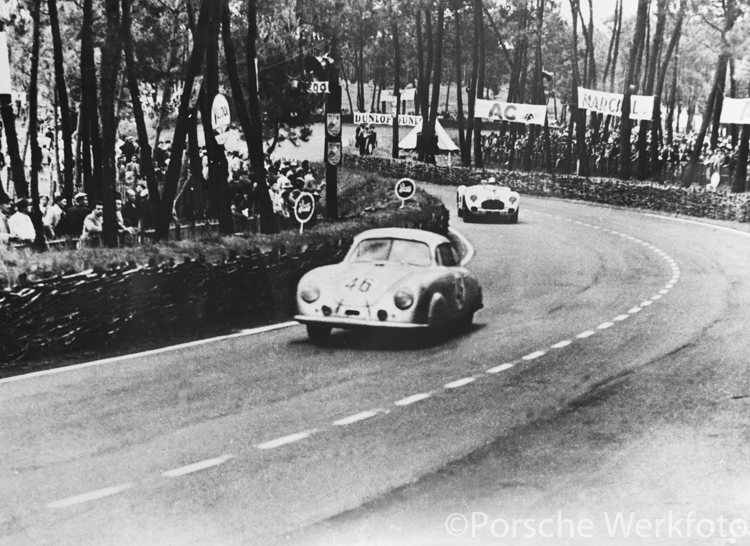

Unfortunately, chassis #054 was substantially damaged in an accident in April 1951, and was still in the factory being repaired at the time of the race in June. Chassis #063 too was crashed and would also not be ready in time for the race, and in its place 356/2-056 (a fourth chassis) was prepared and entered in the race. However, in an effort to simplify their entry for the 24-hour race, the factory overstamped chassis #056 with chassis #063. Although it cannot be confirmed, it is thought that the reason the factory took this step was to avoid having to resubmit paperwork to the race organisers. This was a process used by many other manufacturers, as it was felt they could account for the changes within their organisation more easily. The two cars that started the race, the newly restamped chassis #063, was given the race number 46 while its sister car, chassis #055, received the race number 47.

During practice in the week of the Le Mans race, the number 47 car was badly damaged when it crashed and rolled in heavy rain, and the car was subsequently withdrawn and did not start the race.

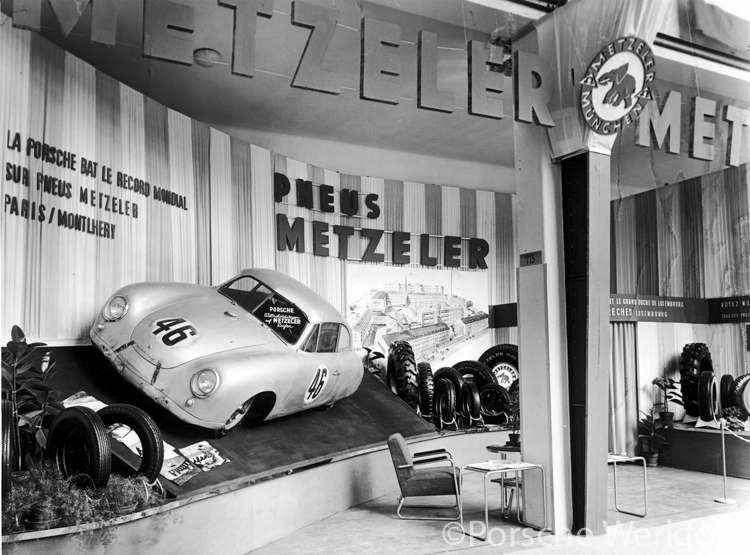

Following practice that was dogged by rain, the race got underway in the dry, but the rain returned after just four hours, and it remained so throughout the night. Despite the difficult conditions in the race, the number 46 Porsche gave an exemplary account of itself, and over the 24-hour period the car ran without a hitch crossing the line in 20th place overall and first in the 751-1100cc class. Having covered a distance of 2840.65km, the French pairing of Auguste Veuillet and Edmond Mouche became the first racing drivers to successfully bring a Porsche race car across the finish line in the Le Mans 24-Hour race, averaging 118.36km/h for the distance. That year, just 30 cars out of the original 60 starters finished the race, as contestants endured rain for two-thirds of the race.

Life after Le Mans

At the end of the year, Porsche shipped three 356 SL cars to its American distributor, Max Hoffman. These three cars were the same three that were earmarked for the 1951 Le Mans 24-Hour race, chassis #054 and #055, both of which had been repaired, and #063. Hoffman sold these three cars to Fritz Kosler, Ed Trego and John von Neumann.

Von Neumann’s large West Coast Porsche dealership in Hollywood, Competition Motors, would come to play a significant role in promoting the Porsche brand through his racing exploits. His first race after acquiring the 356 SL was at Palm Springs in March 1952, and the following month he raced it at Pebble Beach, but retired with brake woes. By the time of his next race at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco, chassis #063 had been given a make-over in red but he posted another DNF due to brake problems. Von Neumann’s first race win came at Torrey Pines in July 1952, which gave Porsche its first victory on American soil.

In a surprise move, von Neumann commissioned Emil Diedt, a very talented metal worker in Southern California, to remove the coupé roof to improve the car’s aerodynamics and to reduce weight. This was an age when a race car had a very short serviceable life, and once it had gone beyond its use by date, it was open to almost any kind of butchery or modification. There was no doubt however that Diedt was a craftsman, and he lopped off the greenhouse of #063 turning it into a roadster, reducing the car’s weight by around 50kg and significantly reducing the frontal area. Von Neumann also removed the front wheel fairings as, despite improving the car’s aerodynamics, they restricted airflow to the front brakes causing them to overheat.

Later that year, von Neumann sold the car to Bill Whittington (winner 1979 Le Mans 24-Hours!), who painted it a blue-grey colour. It then passed through several other owners, before Chuck Forge, an electrical engineer, happened upon the unwanted roadster in 1957. Chassis #063 had by now had an extremely hard life, and so Forge removed the Porsche engine which was on its last legs and he installed a new VW engine, using it as his daily runabout. In fact, Chuck Forge lovingly kept and maintained the little Porsche for the next fifty-two years until his passing in 2009. During this time, he returned the car to its red colour as von Neumann had raced it, and he competed in autocross events, rallies, numerous classic car events and the Continental Sports Car Club tour.

A new life

The next chapter in the life of #063 came about when Porsche connoisseur and collector, Cameron Healy, learned about this little 356 that was looking for a new home. Together with ace Porsche rebuilder, Rod Emory, the two set about finding out more of the car’s history as it became clear that there was a strong possibility that this was the 1951 Le Mans car. Healy purchased the car, and the work of undoing the work of many hands over the last five decades began in earnest. Emory and his team had to strip back the layers of paint carefully in order that the different chapters of the car’s life could be documented. Only then could the work of reconstructing #063 to the specification and standard of the 1951 Le Mans car begin, no small task seeing as the whole roof structure was missing.

Emory was able to carry out a 3D scan of another surviving 356 SL and compare that to photographic evidence that existed. This enabled him to build a wooden buck from which he could reconstruct a new aluminium roof structure. The inner cabin structure had to be built from scratch as the dashboard of #063 had been cut down and modified by one of the car’s previous owners. Emory relied on using time-honoured, old-fashioned metal working techniques, which meant that new body panels for #063 had to be hand-beaten.

Emory’s brief was not to over-restore #063, but rather to finish the car to as authentic a state as possible. This meant that little peculiarities such as the small ding in the rear fender that was left by an overenthusiastic mechanic when changing a wheel during the Le Mans 24-Hours back in 1951, was left in place. A wooden tool chest was made to replicate the one that had been fixed in the place of the rear seats, which would have been used by the driver to carry out any roadside repairs during the race. An additional windscreen wiper arm had been fixed above the driver in the event that the main wiper system failed. A neat air vent was installed just above the front bumper to allow cool air into the cockpit, and could be opened/closed manually by the driver by means of a cable release.

Despite the project not being completed in time for the Rennsport Reunion V in September 2015, such was the importance of 356/2-063 that the owner of the car was invited by Porsche to display it at the event.

It is the goal of the car’s owner to return to Le Mans with 356/2-063, to the venue of the car’s and Porsche’s first race class victory. This would indeed be a fitting journey after 66 years, to see the Porsche 356 SL at Le Mans once again. That is something to look forward to.

Technical specifications: Porsche 356 SL

| Engine | 4-cylinder boxer engine, air-cooled |

| Capacity | 1086cc |

| Bore x stroke | 73.5 x 64mm |

| Valves | 2-valves per cylinder, central camshaft |

| Power | 46bhp @ 4000rpm |

| Carburettor | 2x Solex downdraught |

| Gearbox | Constant-mesh with 4-forward, 1-reverse gears |

| Clutch | Single dry-plate |

| Top speed | 160km/h |

| Suspension: Front | Parallel trailing links acting on transverse torsion bars |

| Suspension: Rear | Swing axles located by trailing links controlled by transverse torsion bars |

| Tyres | 5.00 or 5.25 x 16 by Metzeler |

| Weight | 640kg |

| Length | 3860mm |

| Wheelbase | 2100mm |

| Track | (front) 1290mm; (rear) 1250mm |

| Fuel | 75-litres |

Written by: Glen Smale

Images by: Porsche