Vasily KOSTIN

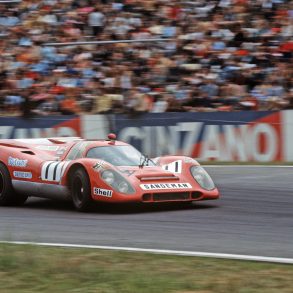

A cage of thin aluminum tubes, lightweight skin, double wishbone suspension and a crazy five-hundred-horsepower engine — this was the legendary Porsche 917 prototype, which forever inscribed the Porsche name in the history of Le Mans marathons. This year, the “nine hundred and seventeenth” turns forty: it’s high time to recall the history of one of the most ambitious and high-profile projects of Ferdinand Piech.

In 1969, Porsche was not the company we know today. The 911 had been in production for only five years and was not yet a legend, and its sporting successes were provided by light, maneuverable, but low-power cars – from the 356 family, the 550 spider model, the 904 coupe with a plastic body. They largely inherited the design of the famous Beetle – from the opposed four-cylinder engines with a volume of 1.1-1.6 liters (although over the years the engine was completely redesigned) to some suspension parts.

In 1964, the ambitious 28-year-old Ferdinand Piech, the same nephew of Ferdinand (Ferry) Porsche who headed the Volkswagen concern in the nineties, became the head of the development department. He wanted not just episodic successes, but to take Porsche to a fundamentally new level! In just two years, under his leadership, first the mid-engine coupes of the 906/907/910 family with six- and eight-cylinder engines were created, and then the three-liter sports prototype 908. The latter initially did not live up to expectations, and in July 1968, Ferdinand Piech and his subordinates took on the development of a new racing car – one that would certainly bring fame and authority to the company.

By the 1969 season, the FIA had just approved new technical regulations for sports cars. There was some behind-the-scenes fuss: in 1966-1967, American Ford GT40 supercars with seven-liter engines from NASCAR cars dominated Le Mans. On the Sarthe circuit with its multi-kilometer straights, the “Europeans” with their low-volume, high-revving engines had nothing to oppose, so the FIA decided to limit the engine capacity of prototypes, i.e. specially built racing cars, to three liters.

But the class turned out to be small, so officials allowed “mixing” serial cars with engines up to five liters into the prototypes – small-scale supercars that private owners already had (Ferrari 250LM, Lola T-70, Ford GT40 in a version with a 4.9 liter engine), and new cars from dwarf British and French firms. The criterion for serial production was a minimum production volume – no less than 50 units. But at the request of the firms, the FIA soon cut it in half.

This meant that it was possible to build a prototype and take it to the LeMans starting line, but to do so, at least 25 cars would have to be built. And that would be very expensive…

But Piech did not hesitate to pay the price.

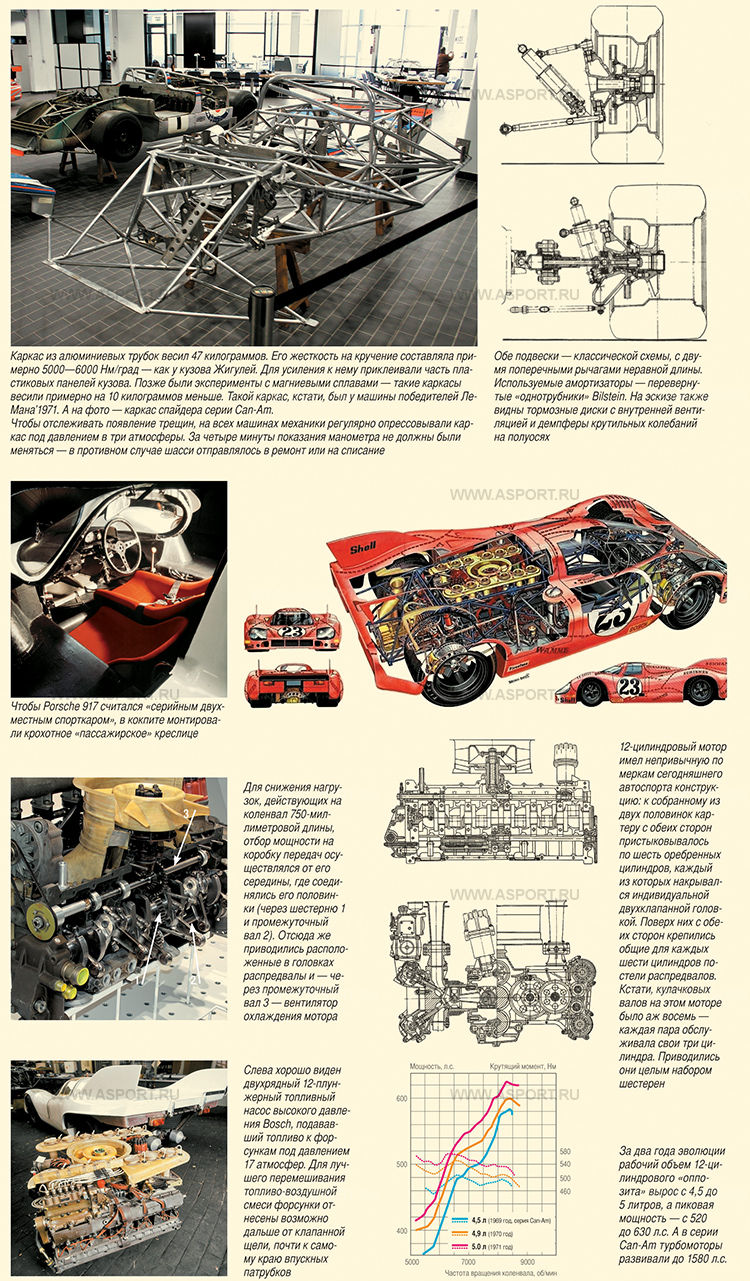

Although Ferrari was already experimenting with aluminum monocoques by that time, the Germans took the “bicycle” design as a basis – this is what the 908 prototype was called for the characteristic shape of the tubular space frame. There was less than a year left before the start, so there was no talk of developing a new engine: designer Hans Mezger took the three-liter, eight-cylinder Porsche 908 engine as a basis (this engine, in turn, is an evolution of the Porsche 804 F1 engine.) The new typ 912 engine turned out to be compact (757 millimeters in length) and light – thanks to the magnesium crankcase and air cooling, it weighed 236 kilograms.

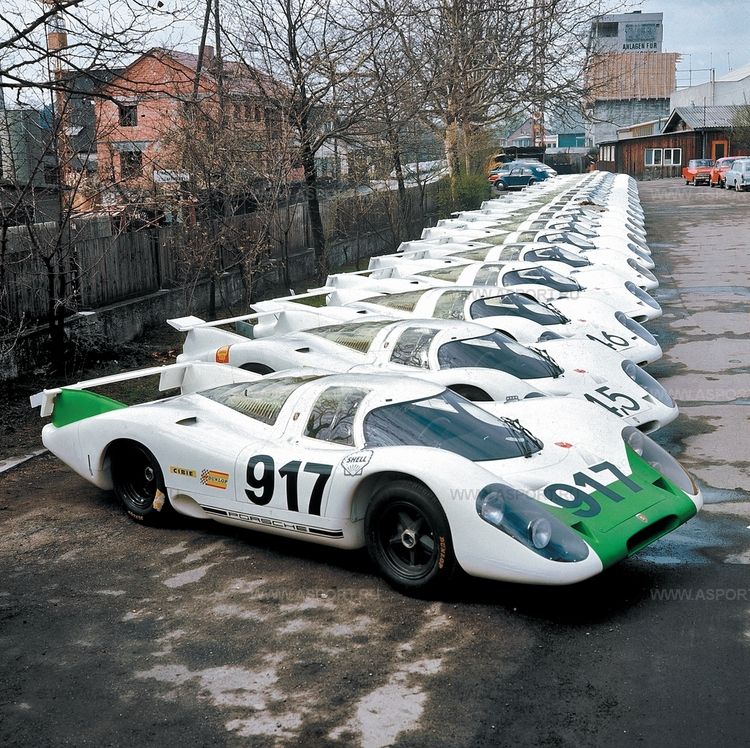

In March 1969, at the Geneva Motor Show, Porsche showed the “serial” 917 coupe for the first time with a price tag of 140 thousand Deutsche Marks – for this money you could buy ten Porsche 911! And this despite the fact that the cost price of the car was much higher…

Having learned what kind of car Porsche was going to homologate, FIA representatives demanded to see all 25 examples at once – it happened that manufacturers “cheated” with body numbers, inflating the circulation and saving on the construction of cars. But in April, in the yard of the Porsche factory, inspector Dean Delamont saw all 25 freshly assembled sports cars!

Haste, as usual, came back to haunt them – during the first tests it became clear that the car could not hold a high-speed straight. For a 520-horsepower car accelerating over 350 km/h, this was literally deadly. At the first stage in Spa, the 170-horsepower less powerful Porsche 908 completed a lap three to four seconds faster and did not require such effort in piloting. At Nurburg, the situation was even worse: half a minute behind. Experienced pilots (Jo Siffert, Gerhard Mitter, Kurt Ahrens, Hans Herrmann) refused to compete in the “nine hundred and seventeenth”, preferring the 908th. Yes, they were brave people, but not suicidal!

Knowing the seriousness of the problem, Porsche chief engineer Helmut Bott did not want to enter the new car in LeMans. But driver Vic Elford finally persuaded him: “Bott was absolutely right about the handling. But I wanted to drive the 917 because I knew I could win!” In the crew with Richars Attwood, he led for 21 hours, but an oil leak caused the clutch to fail – and the daredevils dropped out.

And a private pilot in the same Porsche 917 died. Briton John Woolf bought the “nine hundred and seventeenth” on his own initiative, went to the start of LeMans – and in a dangerous turn Maison Blanche could not cope with the powerful and unruly car already on the first lap of the race. The impact with the fence tore the lightweight aluminum frame in half just in front of the engine shield, the driver died instantly…

Here is what Elford recalled about the car’s behavior: “When on the Mulsanne straight you were approaching a bend in the road at 370 km / h, you had to let off the gas and brake with jewelry precision, otherwise the rear wheels began to overtake the front ones.” At first, they tried to overcome the instability “head-on”, trying out many options for suspension geometry. Nothing helped! The expensive program, on which almost everything was put, was on the verge of failure.

The owner of the British J.W. Automotive stable, John Wyer, saved the “917 project” — the following year his team was to become the main semi-factory team. Unlike the Germans, he had experience working with such powerful equipment — J.W. Automotive won LeMans two years in a row on a Ford GT40 coupe with 4.9-liter engines. Wyer noted that the experimental prototype with an open body had no stability problems. So, it was all about aerodynamics! A sheet of aluminum, a couple of hours of work — and the 917, having received a new engine compartment cover, turned into an obedient car. And the time on the test track immediately improved by three seconds!

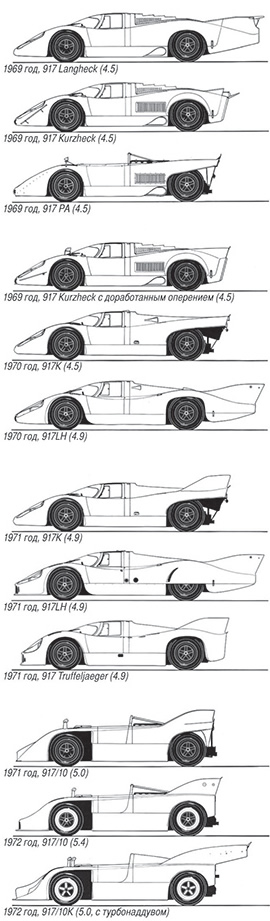

Moreover, from the very beginning, back in 1969, Porsche developed two versions of the plumage: the streamlined Langheck with an extended rear part was intended for the high-speed LeMans straights, the usual Kurzheck — for other tracks. They continued to tinker with aerodynamics in the following years: the Germans experimented with vertical stabilizers and numerous “long-tail” variants, the British with a rear wing in the center of the short car. Incidentally, they abandoned the glass over the engine compartment almost immediately, when the thin plexiglass was broken by the pressure of air sucked in by the engine cooling fan.

The maintenance of a fully factory team required unbearable expenses from Porsche. Incidentally, Enzo Ferrari, who decided to fight the Porsche 917 and built 25 prototypes of the Ferrari 512S, was eventually forced to sell his company to FIAT. And the Germans not only remained undefeated, but also managed not to go broke. True, the last races of the 1969 season, the “production” Porsche 917s reached the status of “private” – at the personal expense of the Porsche family and the brand’s dealers.

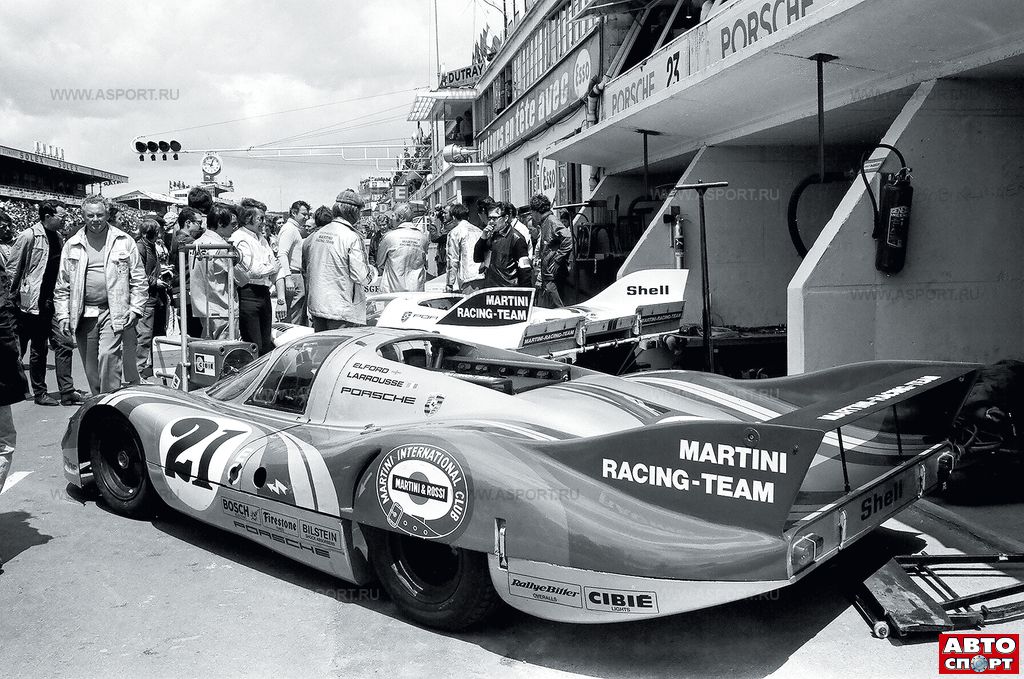

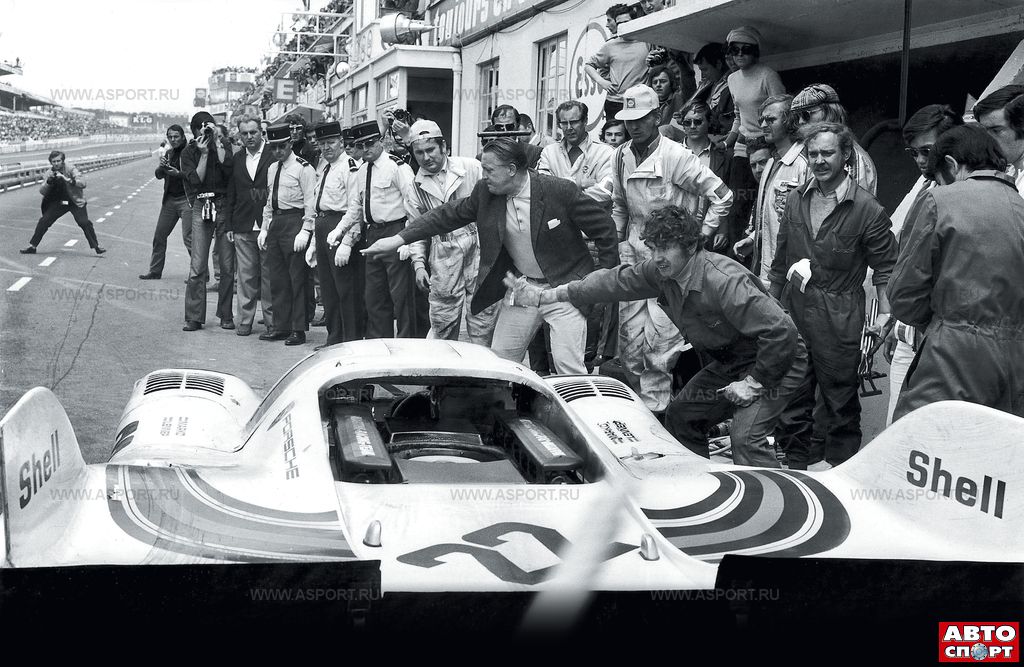

The emergence of a semi-factory team with a powerful sponsor – the Gulf oil company – helped. Winners are lucky! Now the factory workers could think not only about survival, but also pay more attention to fine-tuning the car – and 1970 became a triumphant year for the “917 project”. Most of the races of the sports prototype championship remained with Porsche – however, on the winding Nurburgring and Targa Florio, the pilots still preferred the lighter 908 coupes.

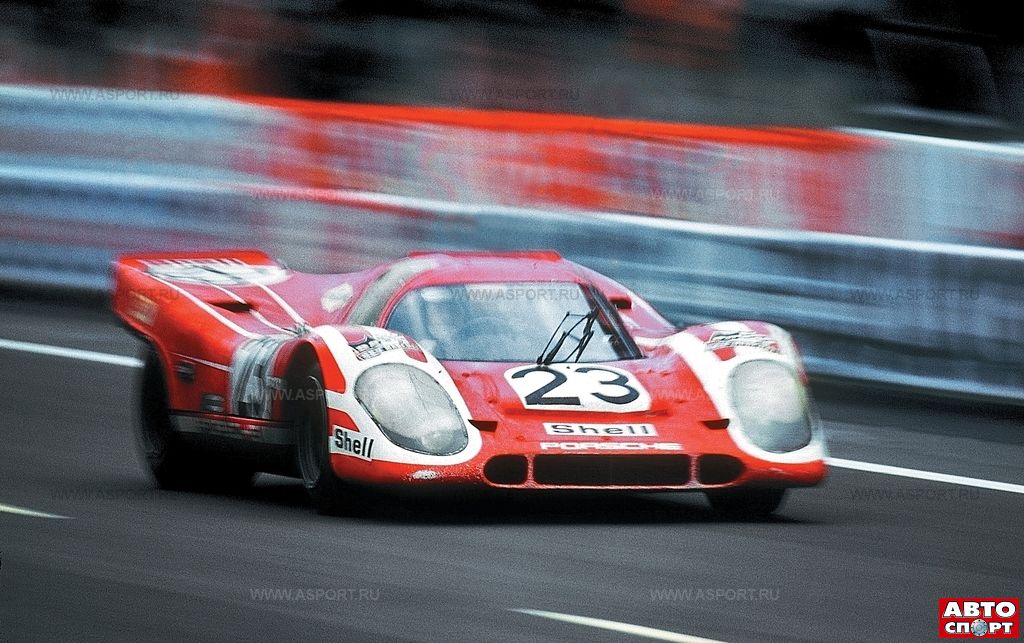

Seven factory-backed 917s and a couple of privateers entered the 1970 LeMans marathon. Among them were two short-tailed 917Ks with tiny rear wings in the center, cars with a new 4.9-liter engine from the Gulf Porsche team, and a long-tailed 917 Langheck with a completely new tail. The old engine’s power was increased to about 550 hp, while the new one produced about 580 hp.

In the heavy rain, only seven crews out of 51 that started finished. In sixth and seventh place in the “Absolute”, behind the prototypes, were the completely production Porsche 914/6 and 911S. Five out of seven Porsches and seven out of eleven (!) Ferrari 512S retired. The entire podium was occupied by Porsche drivers – Ferdinand Piech’s dream came true! “Gold” was taken by Hans Herrmann and Richard Attwood in a Porsche 917K of the Salzburg Porsche team. The crew of Vic Elford – he was the fastest at the wheel of a streamlined 917 Langheck, completing a lap at an average speed of 240.9 km/h – did not make it to the finish line: the Englishman made a mistake in the gear when braking and overrevved the engine, in which a valve broke off.

The irony of fate: most of the victories for the company were brought by the Gulf Porsche team, but LeMans was conquered by them only on the movie screen. In 1970, American actor, producer and amateur racing driver Steve McQueen filmed the feature film Le Mans right during the race. According to the plot, the race takes place in a tense battle with Ferrari crews (which in reality could not get close to the pilots of the German cars) and on the last lap the first two places are snatched by racers in Porsche 917 in Gulf colors. Incidentally, among the nine crews that finished but were not classified in the real LeMans of 1970, there is one, declared by the actor – these are Herbert Linge and Jonathan Williams in the Porsche 908 “cameracar”.

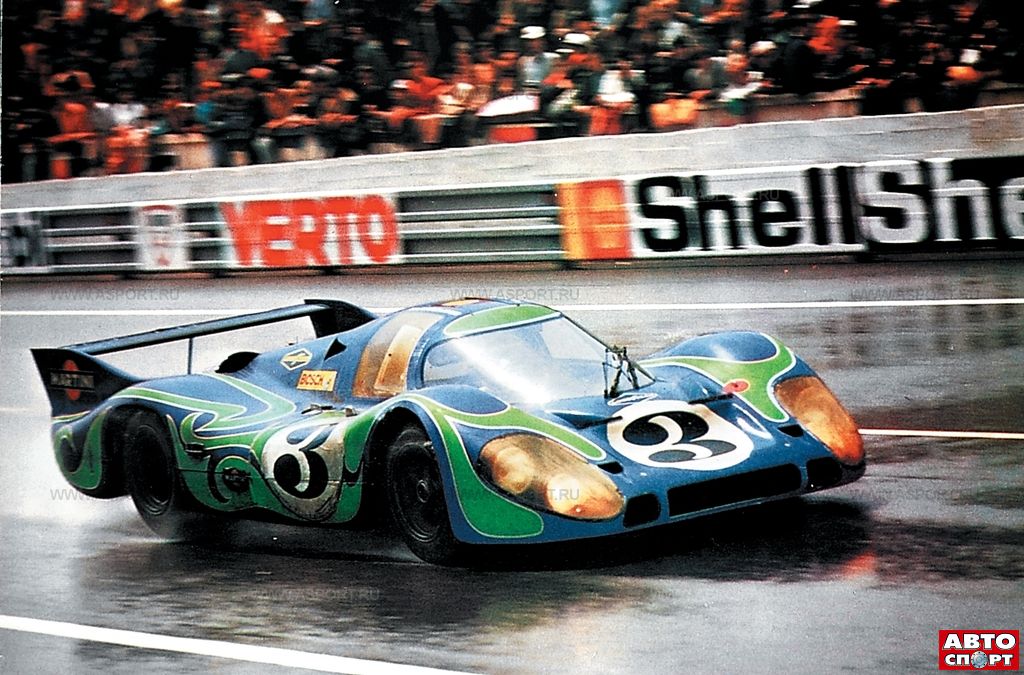

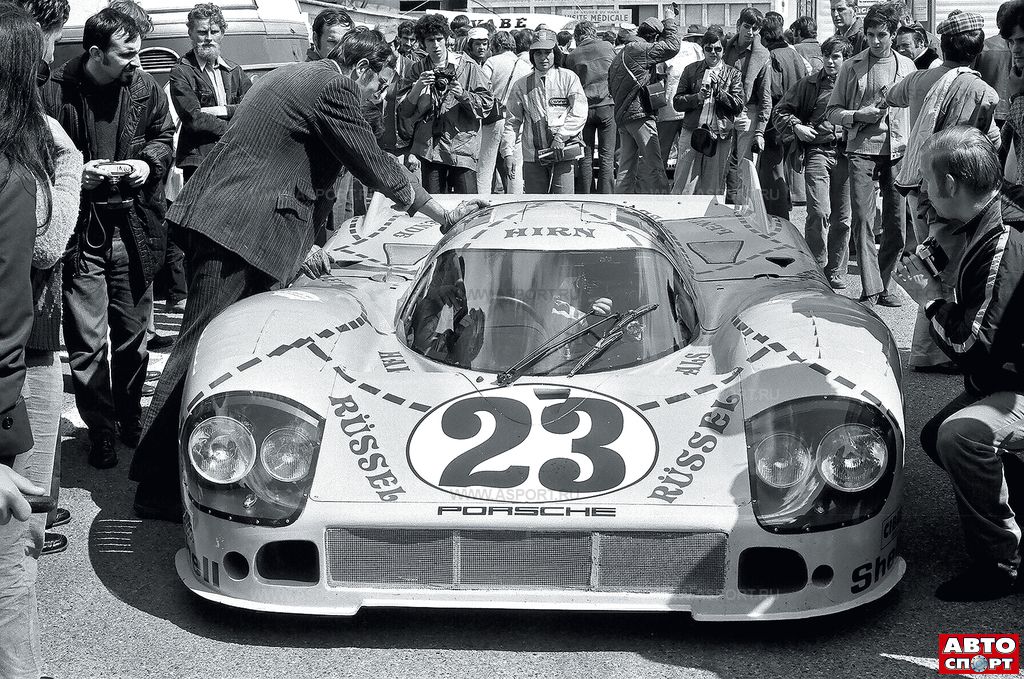

The following year, six factory cars and one private 917 took to the Sarthe circuit – again, all different from each other. Among the trio of Martini Racing cars, the experimental 917/20 stood out, which was supposed to be used in the American Can-Am series. The pink-painted prototype was almost 15 centimeters wider than the standard and had very low ground clearance. Journalists immediately nicknamed it the Pig, while Porsche engineers called it the Truffle Hunter and Bertha the Sow. The wits from the design department even painted a diagram of the butchery on the body, with inscriptions like “Ham” and “Fillet”, and “Brain” above the driver’s seat.

The fastest at first were the sleek “longtails” 917LH, but all three broke down in the race. And after the departure of Joest on the Pig and the breakdown of the private car Zitro Racing, the crew of Helmut Marko and Gijs van Lennep in the “short” car Martini Racing finished first.

Victory again!

The 1971 World Championship also went to Porsche: even the successful three-liter prototypes Ferrari 312P and Alfa Romeo Tipo 33/3 could not keep up with the incredibly powerful and reliable projectile from Stuttgart. But FIA officials, unhappy with Porsche’s dominance, decided to close the loophole of the “five-liter” rules starting with the 1972 season.

It was high time for the Germans to leave on horseback. But Joseph Hoppen, the head of sports projects for the American importer of Porsche, Volkswagen of America, got in the way. In 1969-1970, he lobbied for Porsche to participate in the overseas Can-Am series, where very loose technical requirements for engines reigned, and McLaren prototypes with monstrous eight-liter Chevrolet engines dominated the tracks. The only way to fight them was with their own methods: in the spring of 1971, a Porsche 917 spider with a promising turbo engine was put out for testing. They also tried a 16-cylinder “boxer” with a volume of five liters! But it developed only 690 hp – the same as turbo engines with minimal boost, and the 16-cylinder engine was larger and heavier, and the long-wheelbase chassis built for it was worse in control.

As a result, a Porsche 917/10K with a five-liter turbocharged engine producing about 900 hp was brought to the start of the 1972 season under the Penske Racing team flag — and at the very first race in Mosport Mark Donohue got away from his rivals by a hair! A problem with the throttle valve prevented him from winning — while it was being repaired in the pits, Denis Hulme in a McLaren was ahead.

During tests before the second stage in Atlanta, Donohue got into a terrible accident. The enlarged brake cooling ducts installed at the pilot’s request touched the bonnet latches — and the fairing came unfastened at a speed of 240 km/h, sending the spider into an uncontrolled skid, which ended with several flips! The front of the car was completely destroyed — so much so that the pilot’s legs were outside. Miraculously, he got away with only a broken knee and was forced to recover for more than two months. The car with a magnesium frame was written off. He was replaced at the wheel of the spare turbo Porsche (now with an aluminum frame) by George Follmer, who, together with the returning Donohue, won all the remaining races and destroyed the McLaren team’s five-year hegemony in the Can-Am series.

The following year, Donohue drove an updated Porsche 917/30. The car featured redesigned aerodynamics, a slightly longer wheelbase, and a new 5.4-liter turbo engine. With a boost pressure of 2.7 bar, it developed up to 1,580 hp, although for the race its power was usually reduced to 1,100 hp. Cars with this engine were not equipped with a differential – the “limited-block” ones that were available at the time could not withstand the crazy torque! They say that the prototype accelerated to 100 km/h in 1.9 seconds, and it needed 10.9 seconds to reach 320 km/h. The “maximum speed” reached 420 km/h! Needless to say, the 1973 season also went to Donohue?

Because of its overwhelming advantage, the 917 was nicknamed in the States “the car that killed Can-Am.” And “Unfair Advantage” is the title of M. Donohue’s autobiography, which is also about her. Fuel consumption restrictions introduced the following year led to the Porsche and McLaren teams withdrawing from racing and the series collapsing.

This was supposed to be the last chord in the history of the remarkable sports car. But it wasn’t.

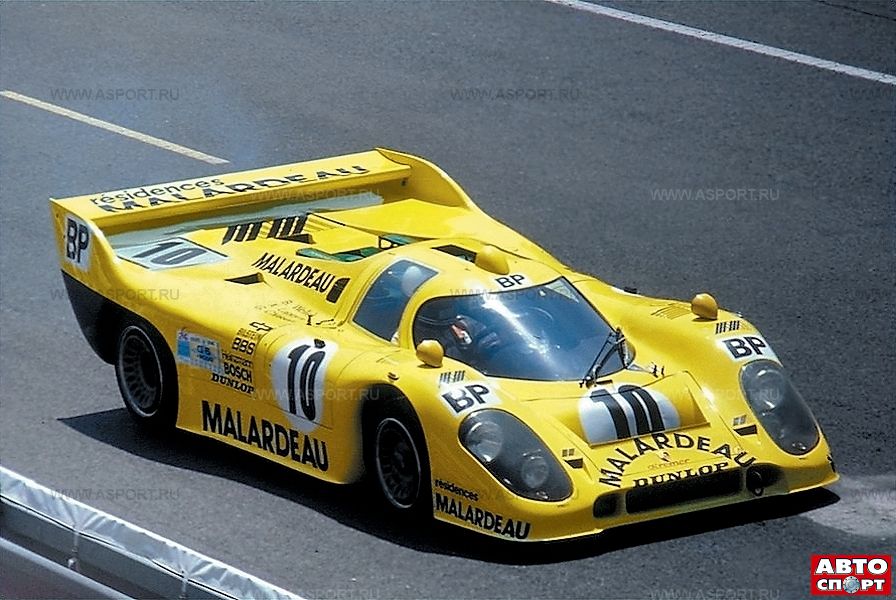

Seven years later, in 1980, “interim” technical requirements were introduced in LeMans for a period of one year — so that teams could painlessly switch from the old sports cars of groups 5 and 6 to the new sports prototypes of group C, the development of which was just beginning at that time. The German Kremer team, known for its successful racing versions of the Porsche 911 coupe, decided to exhibit its own car based on the Porsche 917. Porsche representatives helped with the construction of the car: for example, they handed over the drawings of the frame and helped to buy the engine and gearbox. They say that Porsche knew nothing about the new project of the Kremer brothers, and thought that they were helping to restore one of the historical 917s. The car, built from scratch, had a reinforced frame close in design to the original, a 4.9-liter engine, a suspension modified for modern tires, and completely different aerodynamics.

Unfortunately, the maximum speed was sorely lacking – partly due to the lack of power, but mostly due to the selection of gear ratios. From the lap, the car was seventeen seconds behind the leader in the Porsche 936 prototype… In the race, the Kremer team was in ninth place, but they had not driven even seven hours before they retired due to an oil leak.

The Kremer brothers also entered the car at the start of the last stage of the sports prototype championship, where Bob Wollek was the fastest in qualifying in the rain. In the race, the 917 even led – again, like ten years ago! Alas, not for long – the suspension broke. And this was truly the last race for the Porsche 917.

Ten years, twenty-one million Deutsche Marks and the ability to chart the most profitable course through the thicket of technical regulations. Here’s how one small German carmaker, starting with Beetle-based cars, changed the history of motorsports! Would Porsche be what it is today without the “917”?