From April 18, 1980, to October 20, 1980, ASB Kassel participated in practical testing of the SAVE (Speedy Ambulance Pre-Clinical First Aid) prototype ambulance on behalf of the Federal Ministry of Research and Technology. This ambulance was developed and built by the Porsche Weissach Development Center under a contract with the Federal Ministry of Research and Technology.

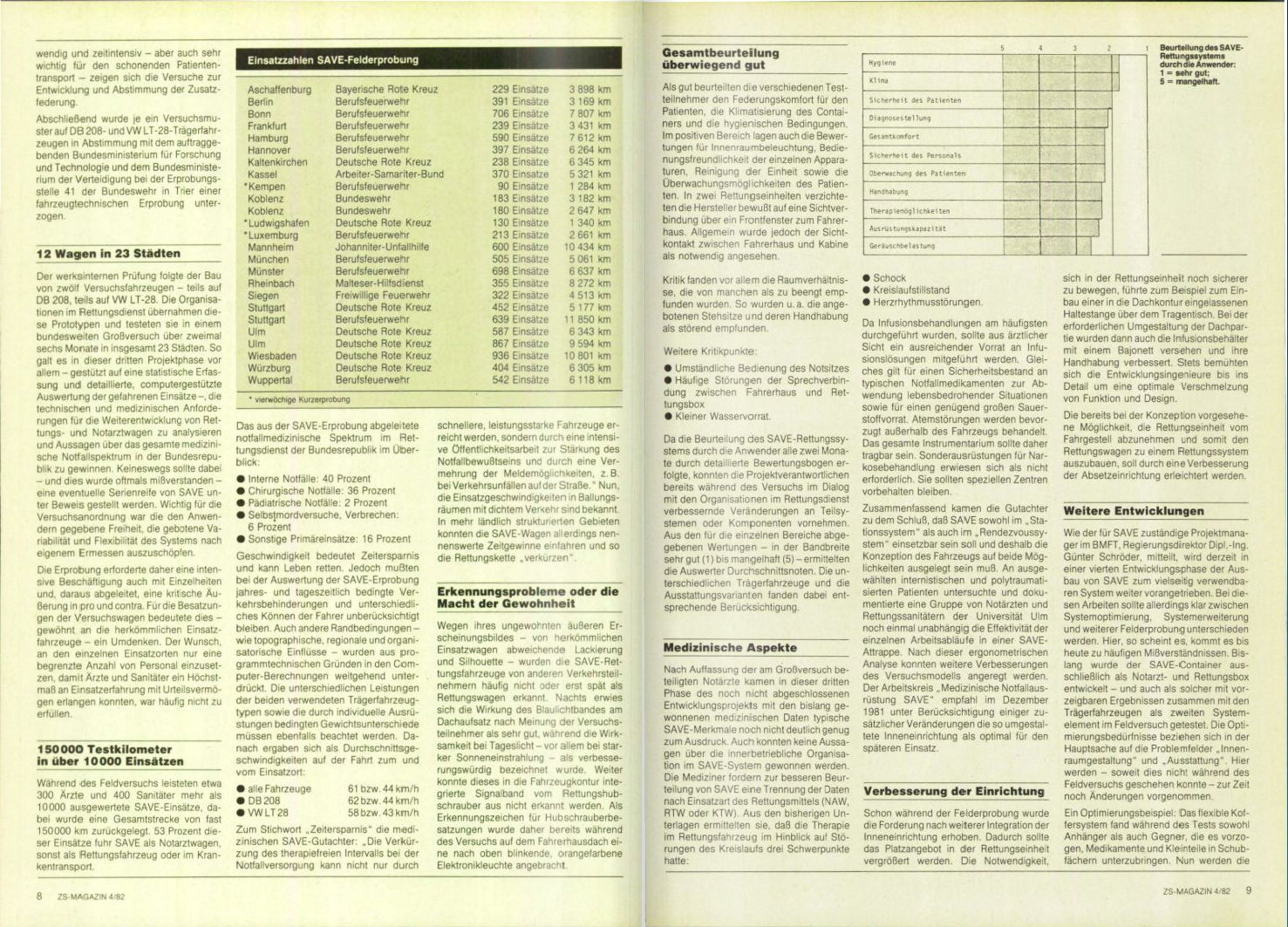

ASB Kassel selected the VW LT31 and MB W208/210 chassis as the vehicle. A total of 12 ambulances were built.

Unlike conventional rescue vehicles, the SAVE plastic rescue module is manufactured using sandwich technology. In emergency situations, this module could be quickly detached from the chassis and transported by tracked tractors, trucks, or helicopters. By connecting several such modules together, they could be converted into a small medical station. Inside, all medical equipment was housed in twelve special containers, including two adjustable and movable seats for doctors.

The purpose of the testing was to thoroughly verify the suitability of the SAVE ambulances and their individual components in an emergency, and thus lay the foundation for subsequent series production of similar ambulances that would best meet the requirements of modern rescue services.

The project was closed at the end of 1982.

Note in Der Spiegel magazine (11/04/1982)

In 1977, Hans Mattefer showed foresight: “If a finished prototype can be presented today,” he warned, “this should not lead to the conclusion that the SAVE rescue system will be available for purchase tomorrow.”

The then research minister’s caution was justified: the question of when the vehicle, grandly dubbed the “ambulance of the 1980s,” would roll off the production line remained open. After a full year of testing, the project has drawn considerable criticism, yet there’s virtually no real interest in the vehicle developed by Stuttgart sports car manufacturer Porsche on behalf of the Bonn company.

Malteser Aid Service has reached only one important conclusion: “The amount of new technology,” summarizes Mario Nowak from the Cologne headquarters, “doesn’t guarantee results.” Hans-Hinrich Mehrkens, an emergency physician in Ulm, reached a similar verdict: “We couldn’t see any significant progress,” he criticized.

Only one customer appears to be still impressed by the research work of Porsche’s technicians: in early November of last year, the Bonn company approved an additional 3.1 million marks for the “optimization and further development” of the vehicle.

Although conventional German ambulances are “recognized worldwide” (Mario Nowak), the Ministry of Research commissioned the Stuttgart company in 1975 to develop “a draft of the basic concept of a modern ambulance for the 1980s.” The estimated cost of one such machine is about 700,000 marks.

Over the next twelve months, a ten-person research team determined that the ideal vehicle should be “efficient, affordable, functional, and versatile.” Porsche’s thinkers also presented a description of the vehicle: according to their findings, the wonder car was to be built modularly and consist of a rescue module and the vehicle itself.

The predictions of then-project manager Ulrich Betz that the research would require more funding proved correct. By federal government order, in 1976, the designers were authorized to build a test vehicle for 950,000 marks, and a year later, twelve prototypes at just under a million marks each. However, the initial plans were far from being realized. It was the innovations developed by the technical specialists that drew the most criticism from experts.

The first problem: the new “doctor’s chairs.” Because the plastic rescue module was too small, as the test report succinctly states, “the doctor and paramedic’s paths intersected, resulting in mutual obstruction.”

The second problem: drivers had difficulty informing other vehicles of their presence and exercising their special rights in traffic due to the new “optical warning device” (patent number P 26 41 006.0), which replaced the conventional blue light signal in the form of a horizontal panel on the roof. The technicians overlooked the fact that the new “optical warning device” was not visible from all sides.

The third problem: the radio link between the driver’s cabin and the rescue module continually failed. “A solution to this problem,” concluded Porsche specialists, “could only be achieved by a complete redesign.”

Moreover, the key feature of this innovative vehicle has yet to be tested: transferring the rescue module from one vehicle to another—the reliably functioning lifting device required for this has yet to be developed.

Meanwhile, Porsche openly stated that the 3.1 million marks approved in November were clearly insufficient for the project to be fully operational. A new interior for the two vehicles, at the request of emergency medical personnel, will cost approximately 250,000 marks each. Furthermore, the funding plan approved by Bonn has not yet included further changes, also referred to as “optimization”: project manager Fritz Hacker announced in November that the 2.8-ton weight limit had already been exceeded during initial testing. To solve this problem, something completely new is needed: “a longer chassis with greater load capacity.” Consequently, the rescue module must be redesigned. Hacker estimates the redesign will take approximately ten months. He admits he doesn’t know how much it will cost to build and test the new vehicles.

But none of this can sway Government Director Günther Schröder, the ministry’s point person for the project. He finds a simple explanation for the widespread criticism: “These days, unfortunately, doubters predominate.”